Article published on April 13th, 2014 in the Flemish newspaper De Standaard by Dorien Knockaert

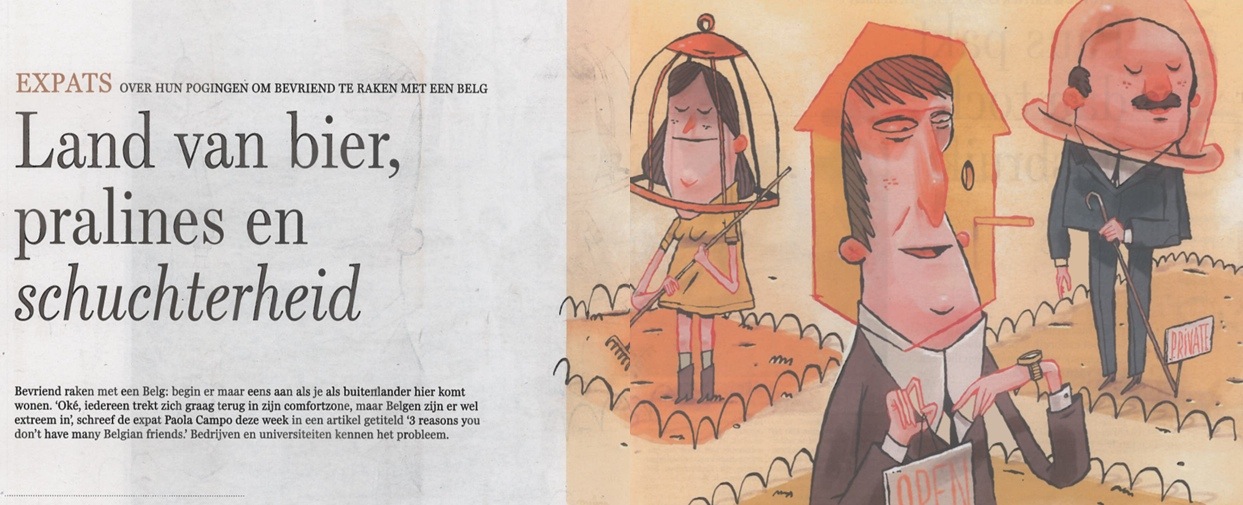

Illustration by Melvin

First: Belgians have always been busy. No nation is so committed to an agenda that everything is fixed weeks in advance. Try to get in between that when you are used to call friends to meet that same evening

Second: Belgians are really, really, really fond of their comfort zone. Instead of moving to the city where they work, they would rather spend hours every day on the road by car to continue to live within walking distance of their family and friends they’ve had their whole life.

Thirdl: Belgians are difficult to interpret. Whether they like what you propose is often a mystery. Or at least they are not expected to show much enthusiasm about it.

Those are, in a nutshell, the “3 reasons why you do not have many Belgian friends”, which Paola Campo wrote this week in an article on Cheesseweb.eu, an online magazine for dedicated for expats in Belgium. Campo grew up in Colombia, studied in Canada, and came to our country ten years ago to work for the international youth organization AIESEC, lives with her Belgian husband in Wezemaal, and today works as an e-learning specialist for a multinational.

“I usually don’t write about topics such as friendship and integration, and I am quite overwhelmed by the many responses the article generated”, she says. “It is something that many expats struggle with, so I wanted to raise awareness. But it was not my intention to present the situation as hopeless, since my life illustrates that good can happen to newcomers here””

“Belgians are indeed warm people, but this is not apparent from the first impression. I was myself lucky to be the newcomer in an office where I worked almost exclusively with Belgians. But it still struck me that even people working at AIESEC, an organization that completely revolves around international exchange, do not seem keen to get to know a foreigner. On the other hand, I grew up in a town in Colombia where we found foreigners nothing short of sensational. We didn’t see may, so whenever someone from abroad came, everyone wanted to get to know him / her. For the Belgians, the situation is obviously quite different. Maybe it’s something historical, there have been so many foreign invaders here that the population attaches extra value to stability. I find it quite paradoxical that this country is so progressive – think of gay marriage, for example – yet craves familiarity so much.”

“Mountain folk” the Belgians

Also among professors and researchers the curiosity is often hard to find, says Vandevelde. “When you’re at a foreign conference, the Flemish professors will have dinner together, safely with each other. But when you travel all the way to let’s say India, isn’t it much more interesting to play cards with international colleagues?

When they come here to join our research projects, they encounter the same disinterest. Even an invitation out of politeness among their peers – it’s a non-optional social convention in protestant cultures – is not obvious.

By now a third of our students is international. I tell them they have to suck it up for three months. After that it will become easier. We are a bit more reserved in our social lives. This is often a typical trait for mountain folk. But it can’t really be due to those few hills in our landscape? (laughs)

It’s also not due to bad will, thinks Vandevelde. “When we for example make it mandatory to co-organize the Christmas party of the faculty with the students from the English-speaking program, they do it. As long as we don’t count on spontaneous interest.”

“You know, we’re not even talking about strong differences in culture. They are mainly students from the south of Europe, very willing to adapt and integrate into our culture, because many of them also hope to find jobs here. The threshold shouldn’t be this high.”

Dirty laundry

To reduce the threshold for our staff, the University of Antwerp has an international staff office since the beginning of this year. “With this we want to support our foreign researchers in terms of administration and also cultural matters”, says employee Tineke De Bock. “We notice that it’s difficult to create a network for them, eventhough it’s in the best interest of the university. When we can bind temporary foreign researchers to us, and when they keep positive memories from their contacts here, then later they’ll be more willing to accept invitations for cooperation and exchange. We would like to increase this return.”

Perhaps the university can gain inspiration from the corporate world, where specific training programs have been developed to soften the culture clash. “Every employee, foreign or domestic, receives two days of intercultural awareness training”, says Hubert De Neve, HR director at the Leuven-based Imec, home to nanotechnology experts with 73 different nationalities. “We didn’t invent this training on our own, it’s largely based on a program that was developed at Shell. when you want to bring the best people here, you have to ensure that differences in mindset don’t create barriers: many companies know this by now. At Imec there is a culture of openness – at the table we spontaneously speak English – but still we perceive notable differences and it’s important to learn how to handle those. For Asians for example, It’s very difficult to criticize research findings, they easily see it as a personal rejection. So we adapt our meeting culture to those things.”

Nele Van Hooste, who delivers the trainings, thinks Paola Campo’s “three reasons why you don’t have many Belgian friends” quite recognizable. “Before the training I always ask participants to write down the cultural differences they notice.” What can we Belgians learn from this about ourselves? That we don’t say hi very often on the streets, don’t often invite people into our homes, are somewhat attached to life around the church tower so to speak. But on the otherhand we stand close together in an elevator or while waiting in line – something that many foreigners consider too close.” Young researchers often are surprised that their Flemish colleagues bring their dirty laundry to their mother, and there’s some amazement over the many sandwich shops where people first take someone’s dirty money, and then make your sandwich with those same dirty hands. But that’s a completely different issue.

Four years of patience

“Well, Belgians will also have issues with us Americans because we are so excessively open” says Diana Goodwin, born in English, raised in Virginia, was an Art Director in Hollywood and now lives in Hasselt with her Belgian husband, where she among others, manages the blog Things You Didn’t Know About Belgium. “But Americans are simply used to seek contact at the first encounter. When I got to know the friends of my husband, I wasn’t treated in the manner that I expected. Yes, I was invited by the other women and friends, but it was different, less intimate. It seems to take years here before you can talk to someone about what’s really keeping you up at night.”

“We’re now fours years later and I’m still patient. I keep telling myself it’s not a disinterest. I think Belgians simply don’t know how to respond to such a spontaneous American. Or that they can’t imagine that this American person could be interested in them. I notice that here as well in the tourism industry: nearly all marketing is oriented to locals, or possibly the neighboring countries. When I say that Flanders should promote its cycling network in the US, that my family loves to come and bike here, nobody believes me.”

0 Comments